GOING BACK TO ROOTS: THANKSGIVING IN AFRICA

GOING BACK TO ROOTS: THANKSGIVING IN AFRICA

The arrival of Thanksgiving is nothing short of a showstopper within the United States. It is one of the most important holidays of the year and a chance to showcase gratefulness for the good aspects of life and the importance of family values, generosity, and sharing food.

Of course, this is a general overview of what has been highlighted as a controversial celebration. Its fairytale-like description of Pilgrims and Wampanoag people sharing meals as a symbolism of unity and peace stands above the near annihilation and destruction of Native Americans’ lives. Subsequently, quite a few people remain skeptical about Thanksgiving as a whole, perceiving it as a holiday made to whitewash genocide under the guise of integration. Native Americans and other citizens have taken over the holiday as a sign of protest, declaring it a day of national mourning and honoring their ancestors and their plight.

However, as accurate as that statement is, Thanksgiving within the United States is not solely a commercial holiday made to appease the white majority’s desire for an idealized past that shrugs off past and present crimes.

Indeed, it has grown into a spectacle of generosity and family unity, and it’s hard to argue against the benefits of promoting generations of a family group gathering together to share a meal. But beyond that, Thanksgiving has its roots in something far more ancient and devoid of political symbolism—harvest festivals.

Thanksgiving is a harvest festival.

Contemporary American history tries to embellish the Thanksgiving mythology to disguise past crimes, but at its core, it was a harvest festival meant to celebrate the successful first crop of the Pilgrims.

In this regard, the act was nothing novel. The act of successfully guaranteeing food for the following months was an event worth celebrating regardless of culture, which means that many cultures have their own “Thanksgiving”-like celebrations taking place whenever their harvest season arrives. It depends on the type of crops, but generally, it takes during the autumn or its equivalent, which means a timeframe between August and November for cultures in the Northern hemisphere.

Naturally, this means many cultures celebrate “Thanksgiving” during the same timeframe as Americans, without being directly related to the imagery seen within the country.

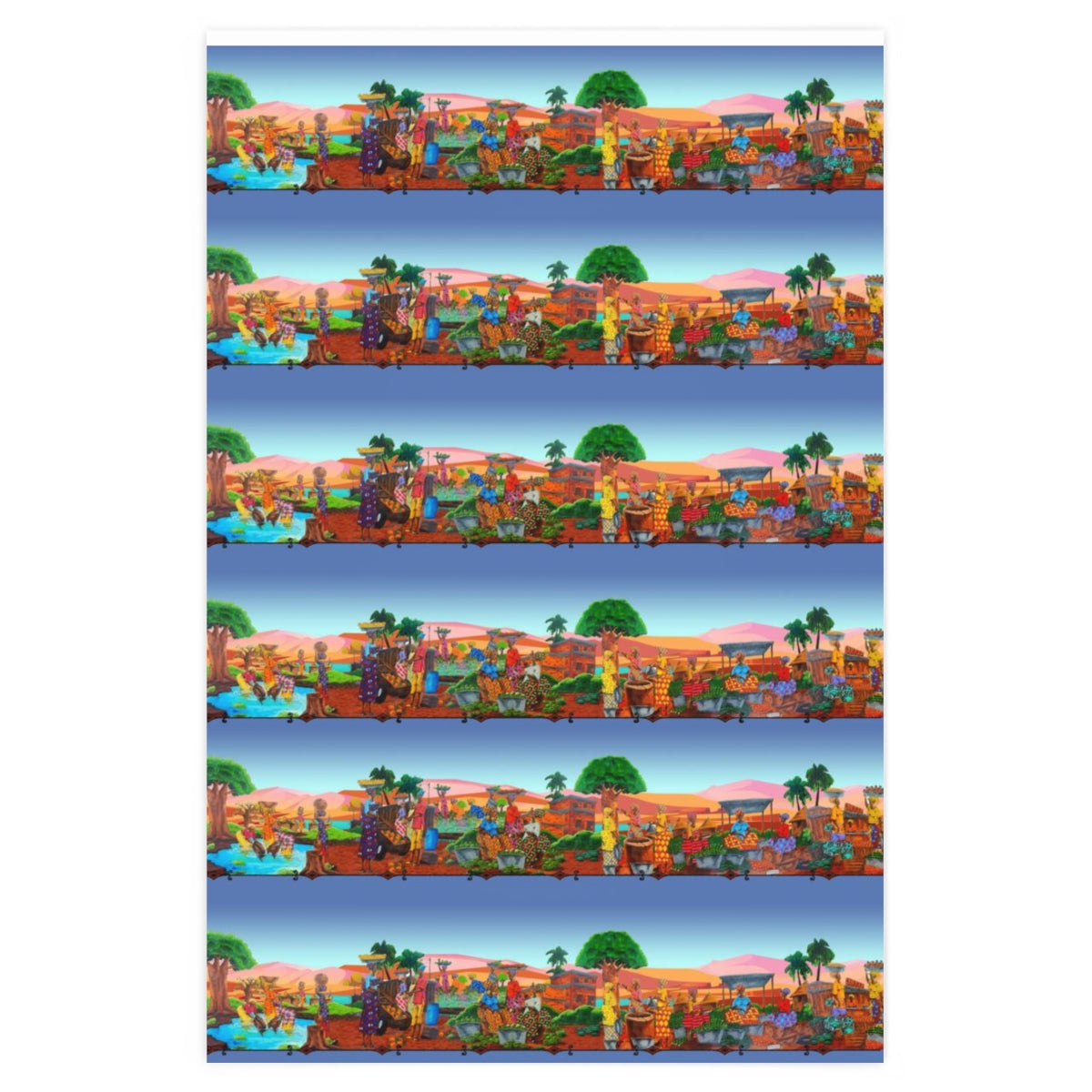

African countries are not the exception, and you can find many different harvest festivals that resemble the American custom, if only by coincidence.

Yam festivals.

Within the United States, traditional Thanksgiving staples—such as potatoes, sweet potatoes, pumpkin, or cranberry—keep that position because they are the main crops of the season within the region. Although food can be imported and available throughout the year nowadays, the tradition of eating local crops during the right season remains.

Africa is no different.

Unlike the United States, the staple crop in large part of the continent is yam—not the sweet potato often labeled as yam within the US market, but actual yam. Sub-Saharan African countries account for nearly all of the worldwide production of yam.

Nigeria, Ghana, and Cote d’Ivoire account are the top three world producers of yam, but other countries such as Benin and Togo also stand out. Likewise, the wellbeing of these countries has depended on yam—for food and economic prowess.

Under these terms, it’s expected that many cultures across these countries have dedicated festivals to celebrate another successful annual crop of this quintessential product. In that regard, Africa has many “Thanksgiving” equivalents.

Iwa Ji (New Yam) Festival.

The New Yam Festival is the peculiar version of a harvest celebration led by the Igbo people, found predominantly in Nigeria and Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, and The Gambia.

Usually taking place in August or September after the first yam crops, the New Yam Festival is a large celebration that is nonetheless enjoyed very locally. Each community has its particular customs, but something remains throughout—the initial ceremony.

Within each community, the oldest or highest-ranking man would offer the yams of the recent harvest to the deities, thanking God for the blessings of food and kindness before distributing them to the rest of the community.

It is undoubtedly a Thanksgiving ceremony—communities are families for societies such as the Igbo, and expressing thanks for the food is at its core what the festivity is all about.

Te Za (Asogli Yam Festival.)

Much like the celebration led by the Igbo people, Asogli Te Za is a festivity meant to celebrate the yam harvest season, taking place during September and led by the Asogli population in Ghana.

Much like the American version of the festivity, Te Za also has roots in a myth. According to the tale, yam cultivation began when a hunter found the tuber during an extreme famine. Instead of bringing it back home, he buried it to retrieve some time later, only to be surprised when, with time, it had germinated and spread.

Considered then a gift of God instead of an accident, Te Za expresses gratefulness to the higher powers for the blessings of abundant food, a resource that brings communities together to share food on the table.

It is, subsequently, a celebration that has the same essence as the American holiday.

Many other versions of this yam celebration take place across Western Africa, and they all find the same roots in yam.

All except one that is far more closely tied to American Thanksgiving than any other.

Liberia’s Thanksgiving.

Liberia is a unique country within West Africa. Founded by freed slaves from the United States and Caribbean countries in the 19th century who took control over the indigenous population, it naturally displays a plethora of customs and traditions from the Americas, alongside the local customs and influences of the neighboring countries and general area.

As such, Liberia stands out as one of the few countries that celebrate Thanksgiving with that name. Likewise, it also takes place during November, although it lands on the first Thursday of the month instead of the last.

The celebrations have similarities, but not many. For example, many Liberians just see Thanksgiving as a day off from work, while others conceive it as a religious holiday meant to thank God for the blessings. Most, however, simply celebrate it at home with their family members while enjoying traditional meals, such as cassava and chicken preparations.

But perhaps most importantly, many Liberians often feel conflicted about Thanksgiving celebrations.

The many struggles and resentments between the elite Congau people (a privileged minority descendant of the freed slaves from the Americas) and the land’s subjugated indigenous ethnic groups are not forgotten. As such, many perceive Thanksgiving as an import—a forced celebration that glosses over history.

“Many who grew up in Liberia or whose families came from that country said they were still wrestling with its history,” says The New York Times, “in which settlers from another continent established control over an Indigenous population.”

It sounds eerily familiar, and it is rather unfortunate that such is the weight of Thanksgiving in the United States and Liberia.

Regardless, it is also a reminder that celebrations can go beyond politics and, behind the makeup façade of fairytales, lies one fundamental truth: food unites us, and the gratefulness over a daily meal is an unchangeably human factor.